Early Victorian times in England were a time of unrelenting change and unrest. Industrialization gave rise to a host of political and socioeconomic problems. While a middle class of merchants and skilled tradesmen emerged to challenge the landed, ruling classes, a burgeoning lower class teetered on the brink of poverty. Caring for the poor and near-poor was the responsibility of the local parish unions, who collected fees from their wealthy to build workhouses and fund other kinds of relief for the poor in their jurisdictions. One of these “other” ways was to provide one-way passage to overseas colonies— thus permanently removing paupers and their families from their rolls. And this is how our Hickson family came to emigrate to Canada.

Ever since Britain became a colonial power, she saw the advantage of exporting (transporting) undesirable citizens to live in her colonies instead of incarcerating them in Britain. These undesirables included political prisoners, defeated revolutionaries (think Scottish Jacobites), criminals convicted of felonies and misdemeanors, and orphans. An orphan could be a child who had lost only one parent, if the state decided the surviving parent could not care for it. In the mid-1800’s, the poor were added to this list.

In 1834, England passed the “Poor Law Amendment Act” which replaced the old poor houses with workhouses. Initially, the Act decreed that assistance to the poor could only be given in workhouses where recipients (and their families) would reside and where they would be clothed and fed and children schooled. In return, all denizens of the workhouse would be required to work for several hours a day. Parishes* were grouped into Unions and each union had to build a workhouse, where conditions were deliberately harsh to deter anyone but the truly destitute from applying for relief. The act was intended to curb the cost of relief, but workhouses were expensive to build and costly to maintain and govern. And many poor went “underground” and lived in horrible conditions to avoid the workhouse. This was especially true for families — if the breadwinner entered the workhouse, his entire family was required to enter as well (and live in separate wings). So, the workhouses really didn’t take poverty off of the streets. (*Parishes here refer to civil parishes and are administrative jurisdictions for local government. While civil parishes often originated from church parishes, they were differentiated in the 19th century.)

So, to reduce the number of workhouses and workhouse inmates, parishes were allowed to consider “outdoor” relief which didn’t involve residency in a workhouse. One very attractive form of outdoor relief was to fund emigration of the “settled” poor within the jurisdiction of the parish union — i.e. those families who could prove settlement (residence) in the district and who were at risk of needing to enter the workhouse as inmates or requiring other parish assistance. It was deemed that the one-time expense of ship fare would be cheaper in the long run than workhouse support. This emigration support was called a “loan”, but in fact, it only had to be repaid if the recipient failed to leave or if they returned to Britain. In 1847 to 1860, Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) was the preferred destination for this state-sponsored pauper emigration.

Why is this bit of history important? Well, in researching our William T. Hickson family, we found that our ancestors were no strangers to the policies of the Parish Union and Workhouse. And the assistance offered was critical to them finding a new life.

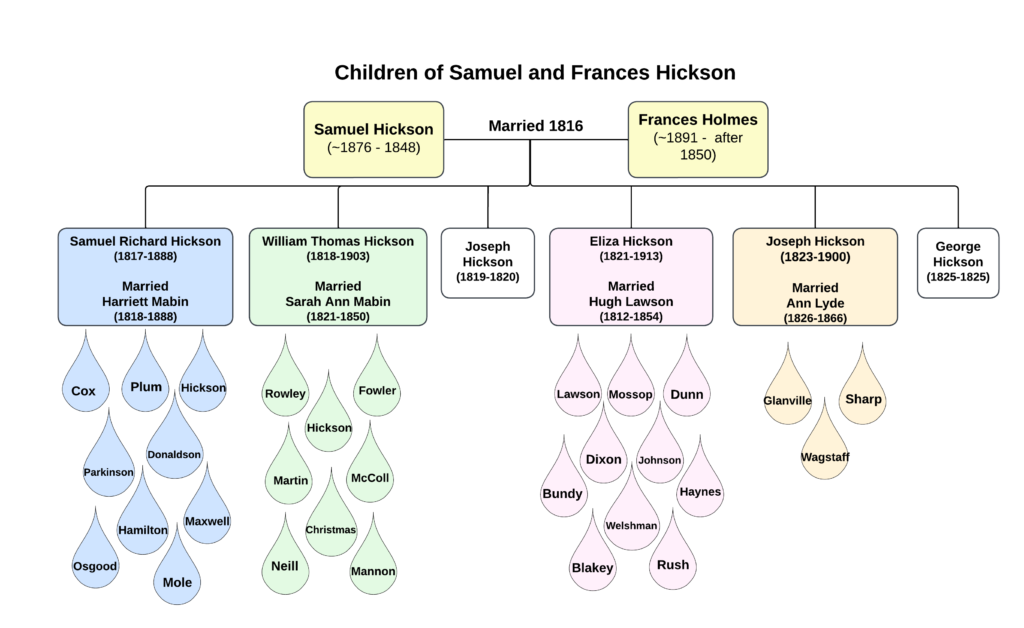

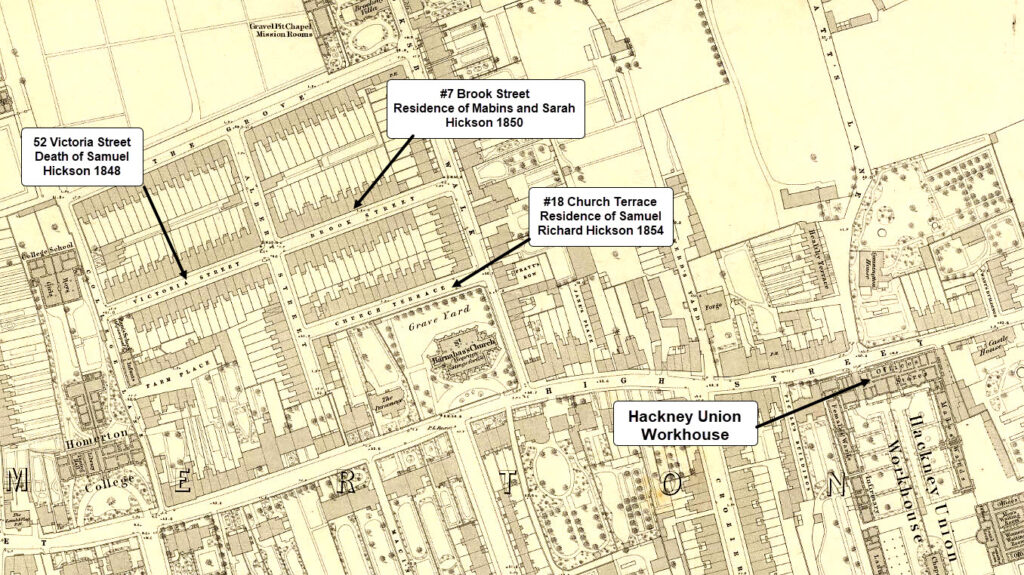

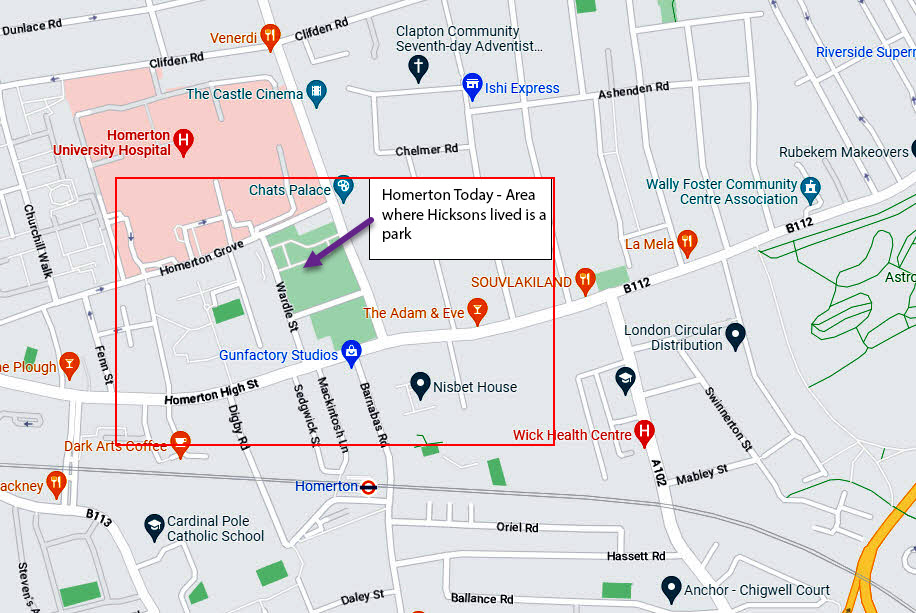

We know very little about William’s father, Samuel Hickson. In all the records associated with his children’s baptisms, Samuel’s occupation was listed as “Gentleman”. That normally suggests an individual with property who doesn’t really have to work. But by the 1840’s, Samuel was a foreman in a White Lead paint factory living in the congested, lower class neighborhood of the Tower Hamlets of Stepney – the center of London’s notorious “East End”. By his death in 1848, he and his children had relocated to the Homerton area of Hackney District – a rapidly growing area on the northeastern edge of the metropolis. We know that his children were not priviledged. Samuel Richard was a maker of hats; William was an oilman; Joseph a grocer; and Eliza’s husband was a tailor.

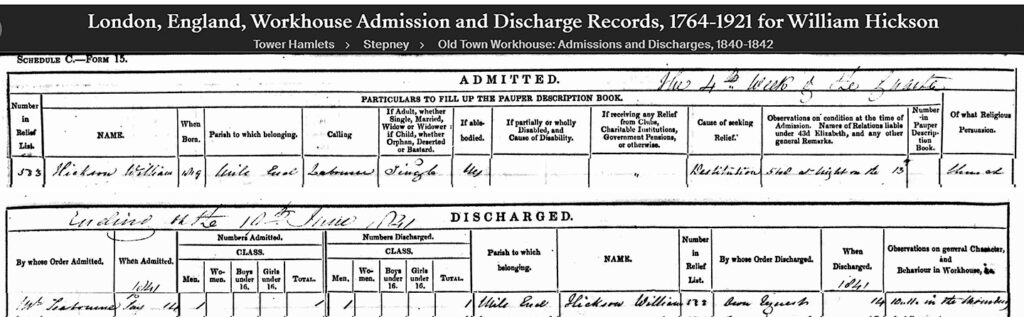

In April of 1841, William Hickson (our ancestor) was admitted at the Old Town Workhouse of the Stepney Parish District near to where he was living on Greenfield Street. He was 22 years old and able-bodied. Destitution was the listed cause. William ended up being discharged at his own request a day later. This was actually pretty common and means he was probably a vagrant looking for a place to stay or he was brought there by a parish constable for drunkeness. Vagrants who found themselves at the door of the workhouse were put into a casual ward which was deliberately the most uncomfortable receiving room in the place — straw and rags for bedding on the floor and a single bucket in the room for a toilet. However, they were allow to discharge themselves before 11 am the next morning without penalty. If they were admitted again within a month, they had to stay for four days in those conditions. William made it out between 10 and 11 the following morning and we have no record that he ever went back. You could say that taking care of vagrants for a night was another form of “outdoor” relief!

Samuel Hickson, the patriarch, died on July 31, 1848, just 3 weeks after his daughter Eliza was married to Hugh Lawson. Hugh and Eliza left for Canada soon after their wedding. We don’t know exactly when they traveled, but they were in Canada by the birth of their first child in 1849. Eliza’s brother, William, went alone to Canada sometime in late 1848 or 1849 (or possibly he traveled with Hugh and Eliza). His youngest son would have been conceived around April 1848. How these three financed their voyage, or whether they traveled together, is unknown. But it does seem likely they used a “loan” from the Parish Union. It turns out the years 1848-1850 were peak years for pauper emigration to Upper Canada. Perhaps, greater availability of Workhouse records in the future will reveal the source of their travel funds.

After William left, life must have been hard for his wife Sarah and her 3 children. It appears that they lived with her parents, Roger and Sarah Mabin in the parish of Hackney, the district of Homerton, near to where the patriarch, Samuel Hickson, died.

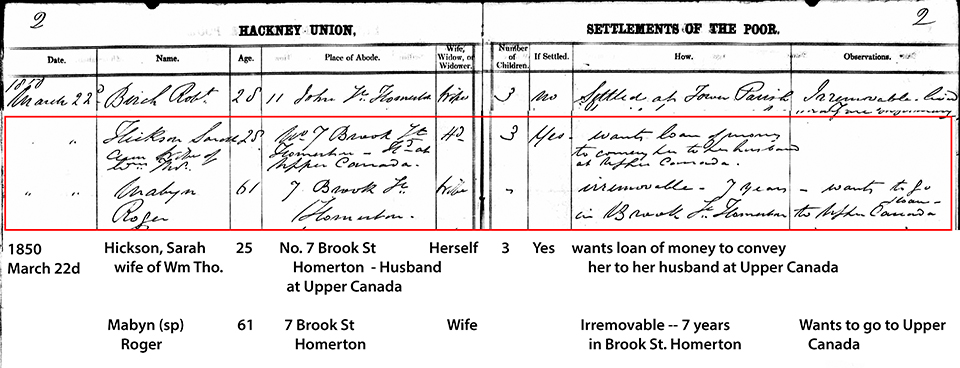

In March of 1850, the daughter, Sarah Hickson, and her father visited the Hackney Workhouse and requested a “loan” to fund transport to West Canada to join her husband. Her father, Roger Mabin, made a similar request. Both of them resided at #7 Brook Street in Homerton. Sarah states she is 25 years old and has 3 children. She requests a loan of money to convey her to her husband in Upper Canada. The entry below Sarah’s is for her father, Roger Mabin. However, it may have been her mother, Sarah Mabin, who was actually present because the word “Wife” is entered in the column for Wife, Widow, or Widower. The entry for the Mabins states that they are ”irremovable” for 7 years at the home in Brook Street. This means that they have lived there long enough to be a permanent member of the parish and can’t be “removed” to another parish. In other words, Roger Mabin qualifies for assistance from THIS parish. The record we have doesn’t record how much they were given, but we do know that Sarah and her 3 children, her parents Roger & Sarah Mabin, and her mother-in-law, Frances Hickson, were on a ship to Canada six weeks later, on May 15, 1850.

The exodus of the Hicksons and the Mabins in 1850 left two of Samuel Hickson’s children still in England. The eldest son, Samuel Richard, and his wife, Harriett Mabin Hickson were married in 1841 and had five children. This family also resettled in Upper Canada in 1855, but their journey had a major speedbump along the way — Samuel Richard spent some time in prison. That story is a whole separate post!

This leaves Joseph Hickson, who married in October of 1855 and had five children. He was a grocer. He never left England. We see him in all British censuses until his death in 1900. We do know that two of his daughters emigrated to Saskatchewan around 1915 and died there. From DNA matches, we find that one of Joseph’s daughters found her way to New Zealand, where her descendants are today.

Joseph was in possession of a letter that his mother, Frances Hickson, wrote in 1850 from the ship that carried them to Canada. When descendants of the Canadian Hicksons visited England in the early 1900’s, the fragile letter was given to them. And that will be the next episode in our Hickson story…..